Companies are key to driving diversity in arbitration

- International arbitration

- Diversity in law

Lack of diversity in the business of law is a well-documented problem. Women make up little more than a quarter of partners at 10 of the most prestigious firms on either side of the Atlantic, according to research by diversity-analytics company Pirical. In the United States, the number of minority partners is 10.9% and racial minorities make up about 8% of UK-based partners at elite British firms. Research also shows that intersectionality (the combination of different elements of a person’s identity which can be subject to discrimination) compounds work-based inequalities. For instance, the 2020 Vault/MCCA Law Firm Diversity Survey, which reflects the responses of 90% of the AmLaw 100, reported that only 3.88% of partners are women in any minority category.

Few would disagree that representation and diversity are important in all aspects of business. However, there is a fundamental benefit in having our courts and tribunals fairly represent the communities they serve: Increased diversity on arbitral tribunals is key to ensuring the integrity and efficacy of proceedings.

The inclusion of diverse arbitrators (including but not limited to women arbitrators) can enhance legitimacy, particularly in investor-state disputes that raise issues of public concern. Generally, tribunals should represent the broad spectrum of stakeholders impacted by their decisions. In addition to considerations of equality, increased diversity improves the effectiveness of tribunals and quality of outcomes by bringing a greater range of perspectives to bear on the decision-making process.

Selecting arbitrators from the usual small pool of mostly white male candidates leads not only to issues of a narrowness of experience and a perceived lack of legitimacy, but also to procedural inefficiencies. These could include a lack of available arbitrators, delays in the rendering of arbitral awards and an increased potential for conflicts of interests—all of which parties will be keen to avoid.

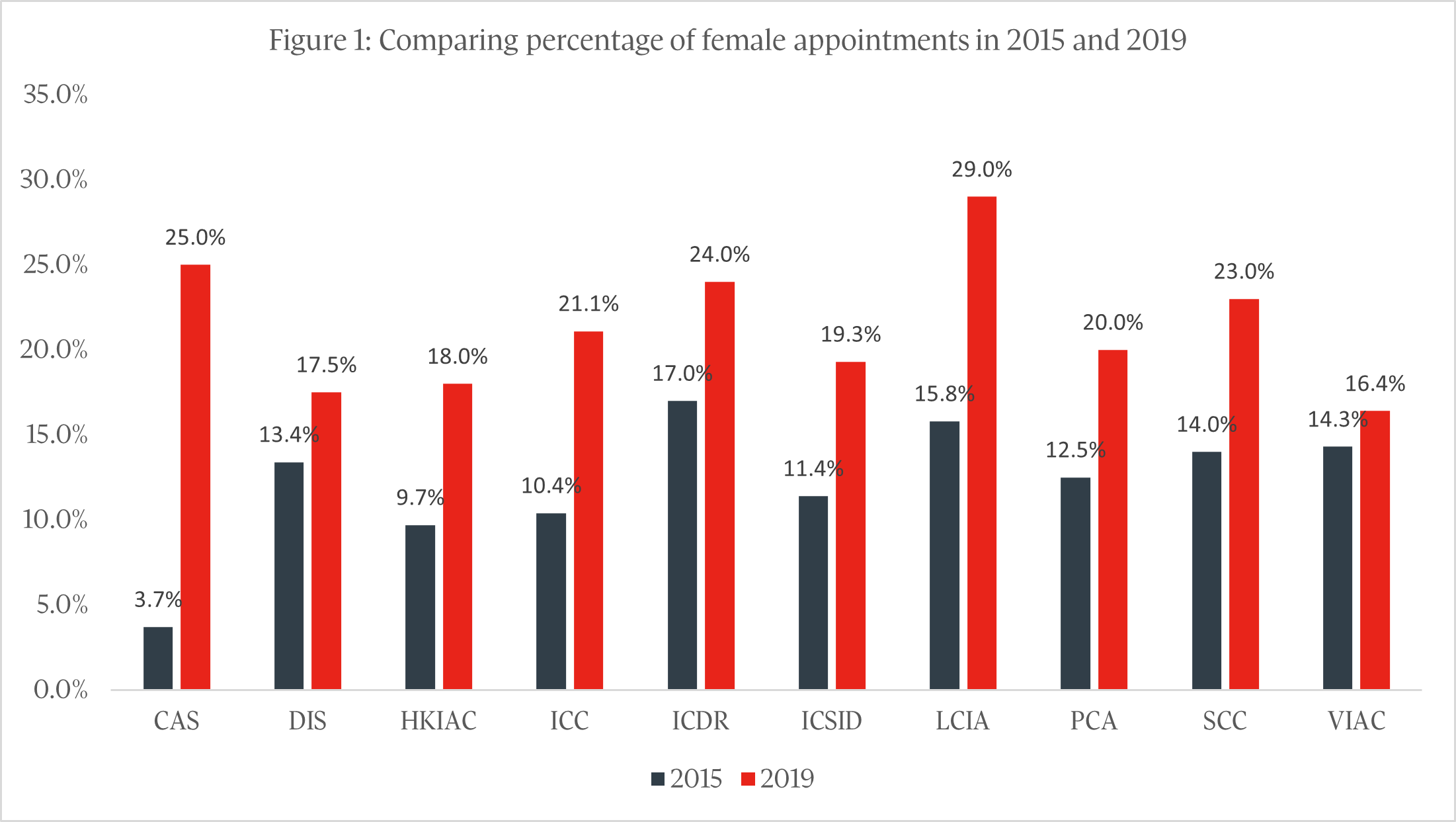

To some extent, we are seeing progress: Gender diversity in arbitration and across arbitral tribunals is increasing. Available data indicates that, before 2012, women accounted for just 3.6% of the total arbitrator population, and 81.7% of tribunals were all-male panels; in 2019, women comprised 21.3% of arbitrators appointed. Recently reported statistics from the International Centre for Settlement and Investment Disputes (ICSID) and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) show improved data for 2020, with women accounting for 31% of overall appointments in ICSID-registered cases and 23.4% of appointments in ICC cases, up from 21% in 2019.

Anecdotally there have also been some notable firsts this year. In May, the first ever all-female ICSID tribunal was constituted and in June, the ICC announced the election of its first female president in its nearly 100-year history.

While these are encouraging milestones, the pace of change remains frustratingly slow. As noted, women account for only about a fifth of arbitrators. With respect to other forms of diversity, tribunals remain remarkably lacking. A 2021 survey by White & Case found that while 61% of respondents agreed that some gender diversity progress has been made in recent years, less than a third felt similarly about geographic, age, cultural, and ethnic diversity.

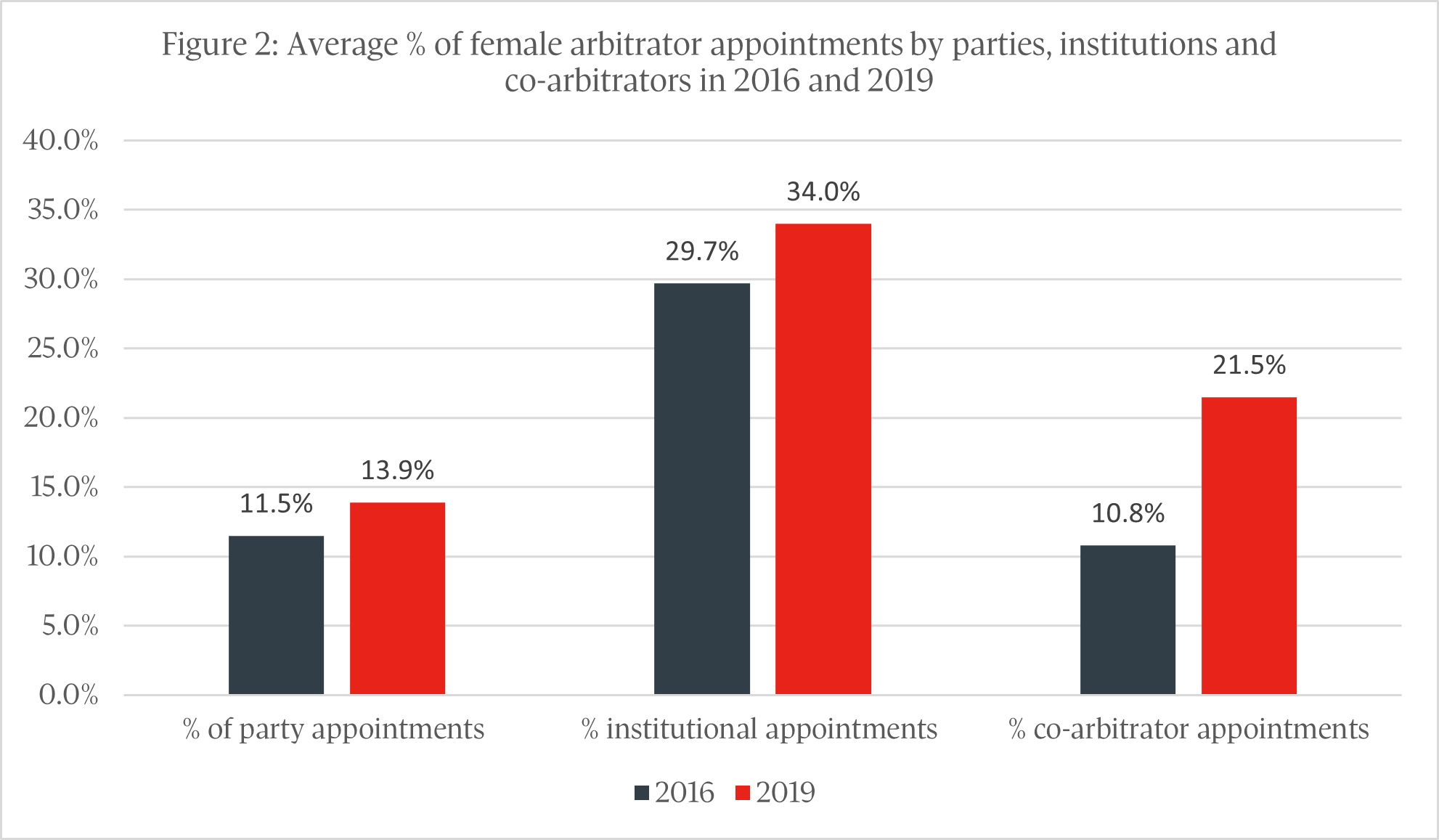

In addition, it is evident from the available data that the increased appointment of women arbitrators has been driven mostly by arbitral institutions rather than by parties engaged in the arbitral process. Progress in party appointments is advancing at a much slower pace; research from the Cross Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity found that in 2019, for example, parties only appointed an average of 13.9% women arbitrators compared to 34% appointed by the arbitral institutions.

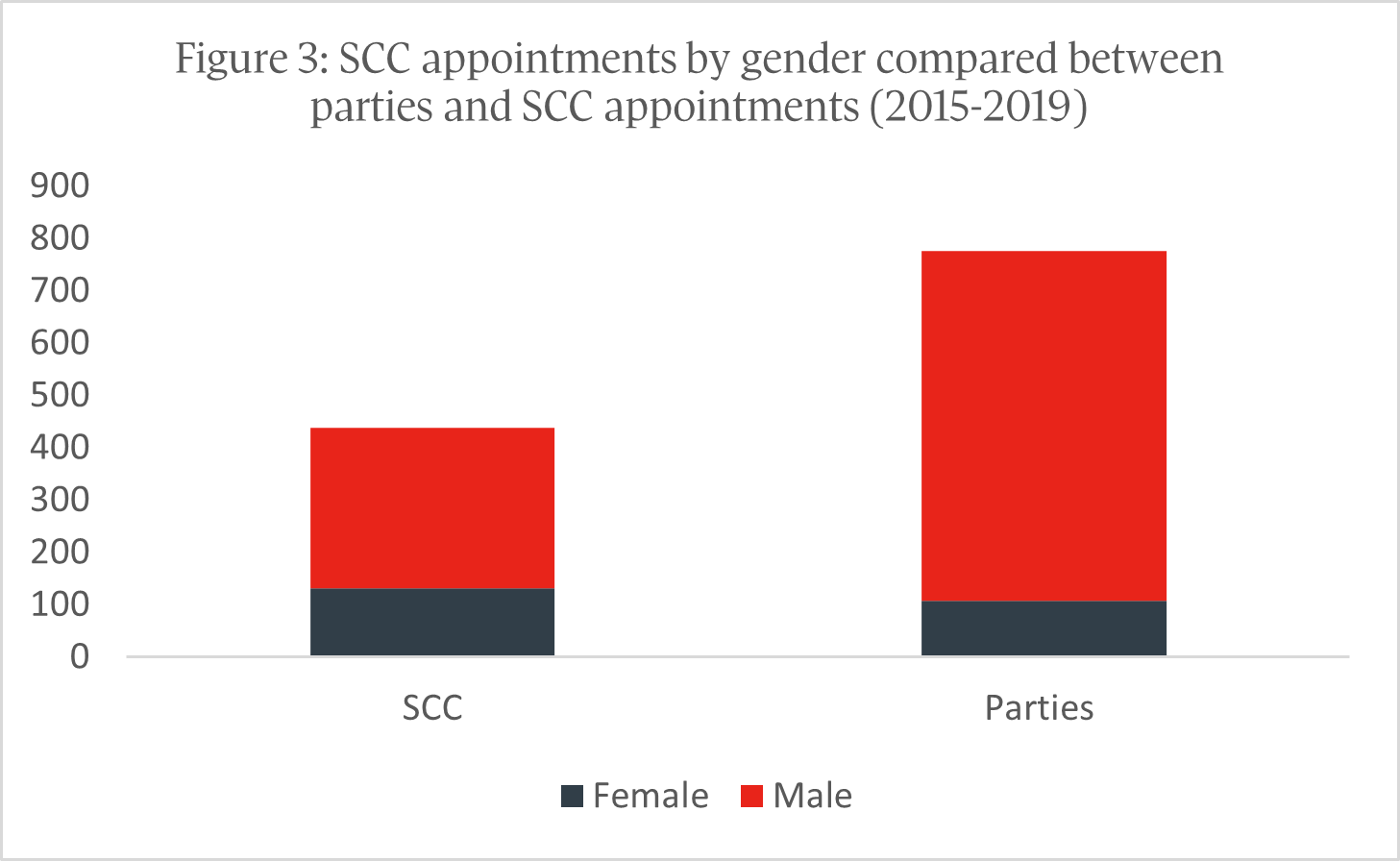

The Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC) analyzed its gender appointment statistics for 2015 to 2019 and found that, while parties were responsible for appointing 62% of all arbitrators, only 14% of party-appointed arbitrators were women. By contrast, 30% of SCC Board appointed arbitrators were women. In other words, while the lion’s share of appointments is made by the parties, the parties are also statistically far less likely to select women arbitrators. The SCC’s 2020 statistics show some progress, with party appointments of women arbitrators increasing to 23%.

In the investment treaty context, the situation is similar. In FY 2020, ICSID had a particularly bad year for gender diversity with female appointments dropping to 14% from 19.3% in 2019. And while respondent states appointed 22% female arbitrators, investor claimants appointed a woeful 2%. The most recent figures from ICSID show a significant improvement for FY 2021, however, with female appointments at 31% overall and the parties appointing 18% (claimant investors) and 38% (respondent states) women.

While these reported increases are encouraging, further progress can clearly be made.

An indicator that corporates are lagging in the push for greater diversity is that only about 7% of the nearly 5000 signatories to the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge (ERA Pledge) are corporations. The ERA Pledge seeks to increase, on an equal opportunity basis, the number of women appointed as arbitrators to achieve a fair representation as soon as practically possible, with the goal of full gender parity.

While corporate parties are most frequently responsible for appointing arbitrators, they may be less familiar with available arbitrator candidates than arbitral institutions and often rely on lists and recommendations provided by external counsel. These lists may be narrower than the broad and balanced view of arbitrator candidates available to arbitral institutions. Yet, corporate parties are ideally placed to apply pressure on their external counsel, through their economic leverage, to incentivize meaningful steps in ensuring diverse tribunals.

Acknowledging that corporates may be less familiar with available arbitrator candidates and often rely on arbitrator candidate lists provided by external counsel, in 2019, the ERA Pledge formed a corporate sub-committee to engage companies, financial institutions and other users of arbitration to raise awareness for it and drive forward its implementation. By signing the ERA Pledge, a company signals its support, including to its external counsel, for a broader and more gender-balanced selection process. In November 2020, the ERA Pledge corporate sub-committee launched the Corporate Guidelines—a set of guidelines specifically designed for corporates to use to implement the Pledge’s diversity aims.

In-house counsel can also significantly influence the diversity of the external counsel teams they engage, and in doing so, enable diverse lawyers, including women, to gain additional experience that may one day lead to arbitral appointments. Many forward-thinking companies are already using a combination of carrot and stick incentives to drive change. For example, in recent years corporations like Microsoft, HP and Coca-Cola have provided stringent diversity expectations for external counsel. The message is clear: Provide us with diverse counsel or risk losing our business.

Another way for in-house lawyers to support diversity is by advocating that, for matters they award to law firms, a diverse lawyer is receiving origination credit or leading the case. This improves underrepresented lawyers’ internal profile within their respective law firms as well as their prospects of being appointed as lead arbitrator in international arbitration proceedings.

Importantly, corporates can ensure that law firms are putting female and racially diverse lawyers into leadership positions through initiatives like The Equity Project. As of December 2020, Burford Capital committed nearly $57 million to back women through The Equity Project—24% of this amount went to support women-led international arbitration claims. Burford has now earmarked a further $100 million for The Equity Project and expanded the qualifying criteria to include racially diverse lawyers. Burford has also committed to sharing a portion of its profits on successful matters with organizations that advance the careers of female and diverse litigators and arbitrators.

Although change has been slow to come, it is encouraging that both law firms and their clients are increasingly aware of the importance and tangible benefits of diversity; with the proper tools, they can work collaboratively to make sure that female and racially diverse attorneys are given the opportunities they deserve to showcase their talents and ultimately achieve better outcomes for everyone involved.

About the authors: Giulia Previti is a Vice President at Burford Capital with responsibility for assessing and underwriting legal risk in investment treaty and international commercial arbitration matters and a member of the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge Corporate Sub-Committee. Ashley Jones is a senior knowledge lawyer at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in London specializing in international arbitration and secretary of the Global Steering Committee and Corporate Sub-Committee for the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge.

This article was originally published in New York Law Journal and can be found here.

Reprinted with permission from the November 19, 2021 issue of New York Law Journal. © 2021 ALM Media Properties, LLC. Further duplication without permission is prohibited. All rights reserved.